FLOATING WORLD CULTURE

Week 2 Class Notes, 7 February 2019

Social Structure and the Samurai

Toyotomi Hideyoshi: Laying the Foundations for the Edo Period

The unification of Japan, following almost 100 years of civil war, was begun by Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582). Part of Nobunaga’s success was due to his tolerance of Christian missionaries and his trade with the Portuguese, allowing him to equip some troops with firearms. He was also willing to promote men based on ability rather than social status. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), the son of a peasant, began as a servant and rose to become one of Nobunaga’s greatest generals.

The move of Hideyoshi from farmer to samurai was not so unusual as it might seem. At the time Japan was an agrarian society and most samurai lived on country estates alongside the farmers, acting as overseers and administrators when their lord (daimyo) did not require their services. There was a close relationship between the samurai and the farmers. Because of the long civil war there was a constant need to replenish the ranks of the samurai, so movement between social classes was necessary.

Hideyoshi succeeded Nobunaga and he had managed to bring all of Japan under his control by 1590. Hideyoshi’s greatest challenge then was to prevent others from usurping his authority and some of the policies that he initiated became important foundations for the Tokugawa government.

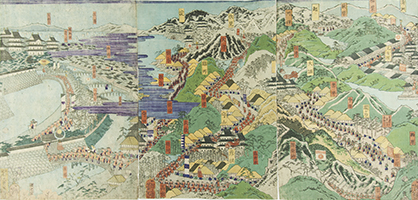

Hideyoshi and His Troops Leaving Nagoya Camp

by Yoshitoshi, c.1860s

After Hideyoshi had conquered Kyushu in 1697 he banned Christian missionaries from Kyushu, where they had a significant presence, in order to prevent an alliance between the Kyushu daimyo and Europeans. Later, in 1597, he executed 26 Christians in Nagasaki.

Hideyoshi distanced the samurai from the farming class, effectively eliminating the peasantry as a source of fighting men by forbidding peasants from owning weapons and encouraging the samurai to move into towns. He introduced a rigid class hierarchy based on the Confucian model. He banned slavery. He ordered a census which had the duel benefit of facilitating taxation and restricting the movement (both social and geographical) of individuals.

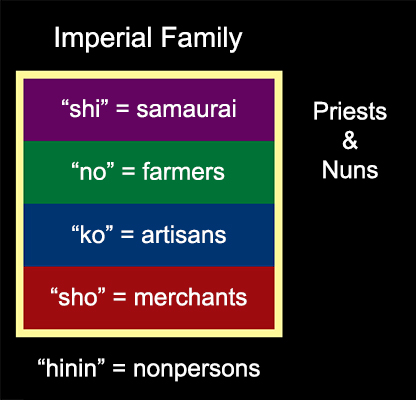

The Class System of the Edo Period

The Tokugawa shoguns, whose rule defined the Edo Period, embraced the rigid social order initiated by Hideyoshi. These social classes were based on a Chinese model where the top class was composed of the gentry, who were gentlemen-scholars who governed, followed by farmers, craftsmen and merchants. The Japanese version was called shi-no-ko-sho, where Shi were the samurai, etc. The theory behind the ranking was that the higher social classes were the more necessary to society. The samurai protected and defended and governed everyone else, the farmers produced the necessities of life, and the artisans produced useful objects. Merchants were at the bottom because they simply traded what others had produced.

The Emperor (who was descended from the gods) and his family existed above and outside the system. Priests and nuns also existed outside the system as individuals from any of the social classes might join their ranks (though the leaders of religious communities would generally have to have come from the samurai class). At the bottom of the social hierarchy were the hinin, or nonpersons, consisting of those who practiced the most distasteful occupations such as waste disposal, prostitution, or acting.

The Samurai Class

The Japanese system of four social classes differed from the Chinese in that the top class, the samurai, emphasized their warrior tradition rather than their role as gentleman scholars. The samurai justified their position at the top of the social hierarchy by virtue of their having a superior moral character. Loyalty and honour were of the utmost importance and samurai were expected to sacrifice their lives for these ideals. Loyalty to one’s lord came before loyalty to family. Samurai were supposed to radiate self-control, dignity and importance. They were expected to be well dressed and to wear two swords, which was both a privilege and a burden. One could not sit comfortably without removing the longer sword (katana) from one’s waistband. In addition to the martial arts samurai were expected to learn poetry and philosophy and to be above the low forms of entertainment enjoyed by the common people.

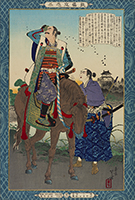

Kajiwara Kagesuye, by Kuniyoshi, c.1844-45

The code of conduct that samurai were supposed to adhere to was called Bushido (the way of the warrior). It emphasized loyalty, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice. It had existed prior to the Edo Period, but it assumed greater significance during the Edo Period as a way to justify the Samurai’s moral superiority and was much discussed and codified in the 17th century.

Suzuki Shigehide, by Yoshiiku, 1867

Bushido encouraged samurai to maintain their military skills. At the beginning of the Warring States period the important martial arts were archery and horsemanship. Later firearms also assumed importance. The concept of swordsmanship as a martial art appeared around the 1570s. From the 1620s martial arts also included: long and short swords, lances, halberds and poles, and the arts of stealth, judo and swimming.

Goto Matabei Mototsugu with Banner of Naito Masanaga

by Yoshitoshi, c.1869-70

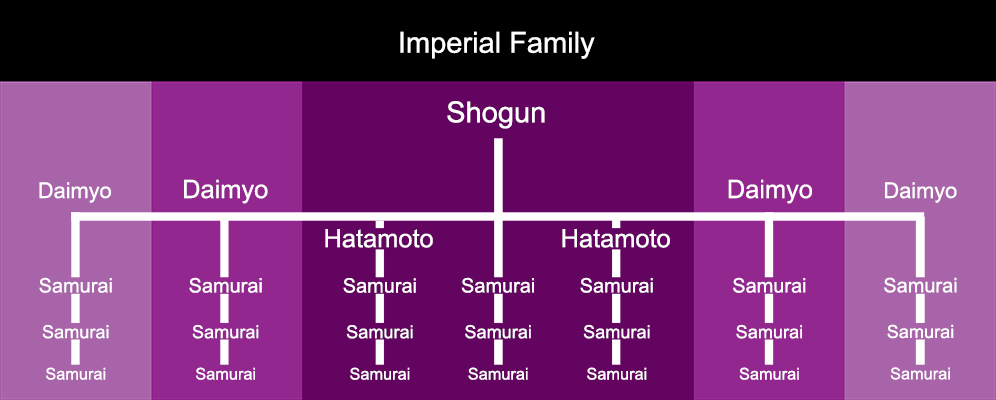

Structure within the Samurai Class

The shogun, ruler of Japan, was the most senior samurai. Beneath the shogun were approximately 260-270 daimyo (the numbers fluctuated), feudal lords who ruled over a particular territory. They owed allegiance to the shogun and were subject to his laws, but within their own territory they could govern as they wished. About 5000 high-ranked samurai called hatamoto reported directly to the shogun. They were bureaucrats and officials. Lower ranked samurai men worked directly for the daimyo, the hatamoto, or the shogun in exchange for a fixed income. They were organized into platoons, but mostly they functioned as bureaucrats.

During the Edo Period the daimyo were divided into two classes: the fudai daimyo and the tozama daimyo. The fudai were the daimyo who had supported Tokagawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), the founder of the Tokagawa shogunate, at the battle Sekigahara in 1600. The tozama daimyo swore their allegiance to Ieyasu after the battle. Daimyo who resisted Ieyasu were exiled or forced to commit seppuku. Ieyasu redistributed daimyo territories to give the fudai daimyo larger fiefs which were located closer to Edo or in other strategic locations. The distribution of samurai mansions within Edo also reflected this difference, with the fudai daimyo residing closer to the shogun’s castle. Some fudai daimyo held high official positions within the government.

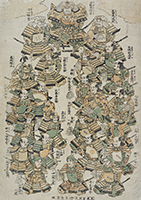

Takeda Shingen (1521-1573), Daimyo of Kai Province, and his retainers

The Tokugawa shoguns faced the same problem that Hideyoshi had: how to prevent daimyo from becoming powerful enough to threaten their authority. One solution was to keep daimyo from amassing too much wealth. Daimyo were required to provide men, materials, or funds for the construction of public works. At the beginning of the period, while the city of Edo and the castle were being constructed, this represented a huge financial burden for the daimyo.

The third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651), Ieyasu’s grandson, instituted two major policies that had profound social impacts. One, a policy called Sankin Kotai, or the System of Alternate Attendance, lasted through to the end of the Edo Period and proved an extremely effective way of keeping the daimyo relatively weak. It also changed the city of Edo quite profoundly and Japanese society in general.

The System of Alternate Attendance

Sankin Kotai, the system of alternative attendance, was made mandatory for tozama daimyo in 1635 and for fudai daimyo in 1642. Daimyo wives and heirs were required to reside full-time in Edo, effectively hostages of the shogun. (This idea of keeping daimyo families as hostages had been introduced by Hideyoshi and continued by the Tokugawas) The daimyo themselves were required to spend 50% of their time in Edo along with a number of their samurai retainers (for military service to the shogun should it be required). Most daimyo spent alternate years in Edo, but those whose domain was close might move back and forth every six months. For large domains this meant up to 2000 people moving back and forth across the country on a regular basis. One consequence of this was the development of a better system of roads and facilities, such as inns, for travellers.

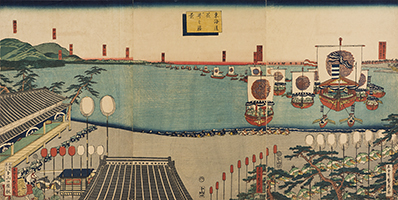

A Daimyo Procession on the Kisokaido Road, by Yoshitoshi, 1865

The social rank of the daimyo dictated the size of his procession and the modes of transportation used. Rank had to be displayed. The rank of senior samurai determined the colours and designs of their clothing, and even the methods and ingredients employed in manufacturing various goods consumed by them. Even the borders of tatami mats in Edo castle varied according to the rank of the officials who sat on them.

View of Arai on the Tokaido, by Sadahide, 1863

Most daimyos maintained three residences in Edo: their own large mansion, a smaller complex for their heirs, and a country retreat outside the city for the summer. A daimyo’s rank determined the shape and size of his Edo residence, including the style of architecture and materials used in buildings and gardens, as well as furnishings. The majority of a daimyo’s samurai retainers who accompanied him to Edo lived in barracks that formed the outer walls of the mansions. If these men were married their wives generally stayed at home. Samurai retainers were paid in units of rice called koku (one koku of rice fed a man for one year) three times per year, so their income fluctuated with the rice market and rice harvest. If a daimyo was undergoing hard times the wages of his samurai were cut. By the middle of the 17th century some samurai were so impoverished they were obliged to sell their possessions or borrow money from merchants.

Katsumoto leaving the Osaka Palace, stopped by Shinegari

by Toshikata, 1888

Edo was a city like no other in Japan. Because of the presence of the shogun’s government and because of the system of alternative attendance, the samurai were disproportionally represented. Japan’s population, c.1700, was approximately 20 million people, out of which approximately 4 million were samurai. In Edo, with a population of about one million people, approximately 50% were samurai.

Foreign Policy: Sakoku

The other major policy introduced by Tokugawa Iemitsu was a severe restriction on foreign influence that came to be called sakoku, or closed country.

The first Portuguese had arrived 1543 and the Spanish in 1584. They brought trade goods from Europe and China and they brought Christian missionaries. This relationship was generally cordial in the early years, but as mentioned earlier, Hideyoshi began to restrict the activities of missionaries.

Arrival of a Portuguese ship, 1 of a pair of folding screens, c1620-40

In 1609 the Tokugawas established trade relations with the Dutch, a relationship that was to have lasting success because the Dutch did not bring missionaries. Christians were a threat because their supreme authority was the Christian god and god’s earthly representative, the pope. This undermined the authority of the emperor and the shogun. Also, although neither the Portuguese nor the Spanish interfered in Japanese politics, the threat was always there.

The Spanish were expelled in 1624 and the Portuguese in 1638. Christianity was made illegal. Missionaries were expelled or executed if they failed to leave. Converts were forced to recant or be executed. Japanese who went abroad faced execution if they returned.

The Tokugawas permitted trade with the Dutch and Chinese, but only through one port. Each nation had its own island in Nagasaki Bay where they were allowed a small settlement to facilitate this. These were not colonies as only men were permitted to reside there. There was also some limited trade with Korea during the Edo Period, but this was through Tsushima, which was closest to Korea, and via trade missions and trading posts at Pusan and Choryang.

As a result of this policy of seclusion the majority of the Japanese people had no contact with foreigners and there were minimal foreign cultural influences. The Edo Period was a time of incredible growth in uniquely Japanese arts of all kinds.