FLOATING WORLD CULTURE

Week 4 Class Notes, 21 February 2019

The Ako Incident

At the beginning of the 18th century an event occurred that helped to support the samurai’s claim to moral superiority through bushido. It was called the Ako Incident.

On April 17, 1701, the Daimyo of Ako, Asano Naganori (1667-1701), attacked Kira Yoshihisa (1641-1703), the shogun’s master of etiquette, in the shogun’s palace. The law strictly forbade the drawing of a weapon, or engaging in a fight, within the palace grounds. The Daimyo of Ako was immediately arrested and ordered to commit seppuku that day, and did so. On April 18th the order went out to confiscate all the Asano property. This dispossessed the Asano family and left all their samurai retainers unemployed. “Ronin” means unemployed, so the Ako samurai became ronin.

The attack in the palace

Chushingura Act 3

by Kunisada, 1847-48

Asano, the Daimyo of Ako, did not disclose his reason for attacking Kira. As Asano would have understood the consequences of his act, it was assumed that he must have been provoked by Kira, in which case Kira would have been a party to the fight within the place, making him guilty as well, but Kira was never charged with a crime.

Asano had approx. 270 samurai retainers. The most senior was Oishi Kuranosuke (1659-1703). On May 26th Oishi and the Ako retainers surrendered Ako Castle and the former Ako samurai dispersed. Oishi secretly lead a group of 46 of these men, including his own son, in planning and executing an attack on Kira. The majority of the Ako samurai did not join the vendetta. Asano had broken the law and this type of vengeance was forbidden.

Oishi Kuranosuke (1659-1703)

by Kuniyoshi, 1852

From the collection of the MET

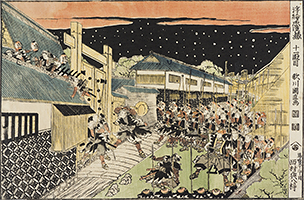

On the night of January 30th, 1703, the Ako ronin attacked Kira’s mansion (the 14th day of the 12th month of 1702 according to the Japanese calendar of the time). Kira had approximately 180 samurai retainers. The attack began with a small advance group of ronin scaling the wall of Kira’s compound. They were able to lock most of Kira’s samurai in their barracks.

The Ako Ronin break into Kira’s Mansion

Chushingura Act 11

by Kuninao, c. 1811

During the attack 14 of Kira’s samurai were killed, 3 of Kira’s servants were killed, and many were injured. None of the ronin were killed or seriously injured. At the time of this attack the oldest ronin was 78 and the youngest, Oishi’s son Chikara, was 15. Chikara would be 16 by the time of his death.

The Ako Ronin capture Kira

Chushingura Act 11

by Hiroshige, c.1835-39

The ronin found Kira and beheaded him. Forty six of them walked through the streets of Edo to Sengakuji Temple, an approximately 2 hour walk. They washed Kira’s head and placed it on Asano’s grave, along with a note and the blade Asano had used for his seppuku. They then waited for the authorities to arrive and surrendered.

The locations of Kira’s house and Sengakuji Temple

The Ako Ronin bring Kira’s head to Asano’s grave at Sengakuji Temple

by Kunikiyo, c.1857

This document was left with the head:

"The 15th year of Genroku, the 12th month, and 15th day. We have come this day to do homage here, forty-seven men in all, from Oishi Kuranosuké down to the foot-soldier, Terasaka Kichiyémon, all cheerfully about to lay down our lives on your behalf. We reverently announce this to the honoured spirit of our dead master. On the 14th day of the third month of last year our honoured master was pleased to attack Kira Kôtsuké no Suké, for what reason we know not. Our honoured master put an end to his own life, but Kira Kôtsuké no Suké lived. Although we fear that after the decree issued by the Government this plot of ours will be displeasing to our honoured master, still we, who have eaten of your food, could not without blushing repeat the verse, 'Thou shalt not live under the same heaven nor tread the same earth with the enemy of thy father or lord,' nor could we have dared to leave hell and present ourselves before you in paradise, unless we had carried out the vengeance which you began. Every day that we waited seemed as three autumns to us. Verily, we have trodden the snow for one day, nay, for two days, and have tasted food but once. The old and decrepit, the sick and ailing, have come forth gladly to lay down their lives. Men might laugh at us, as at grasshoppers trusting in the strength of their arms, and thus shame our honoured lord; but we could not halt in our deed of vengeance. Having taken counsel together last night, we have escorted my Lord Kôtsuké no Suké hither to your tomb. This dirk, by which our honoured lord set great store last year, and entrusted to our care, we now bring back. If your noble spirit be now present before this tomb, we pray you, as a sign, to take the dirk, and, striking the head of your enemy with it a second time, to dispel your hatred for ever. This is the respectful statement of forty-seven men."