FLOATING WORLD CULTURE

Week 6 Class Notes, 7 March 2019

Other Popular Pastimes

Puppets

Puppet entertainments predate the Edo Period, going back at least to the 8th century, but the style that is called bunraku and is still practiced today developed during the early 1700s. During the preceding century itinerant puppeteers performed with several puppet types, all controlled by a single operator who would usually be hidden from view. Stages were temporary and simple affairs. The musicians and vocalists who accompanied the puppets were also usually hidden from view.

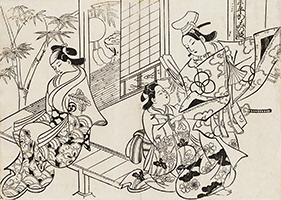

Puppet player holding a puppet dressed as a courtesan

By Kiyonaga, c.1775

The foundations of the modern style were laid in Osaka in the 1680s when the great playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) collaborated with the chanter Takemoto Gidayu (1651-1714). Gidayu’s style of chanting, in which his songs provided a narration for the story, but he also voiced dialogue for the characters, was so popular that subsequent performers imitated his style and it became the standard.

Scene in the Dressing Room of a Puppet Theater

table of contents for the series Famous Scenes from Japanese Puppet Plays (Yamato irotake)

By Masanobu, c.1705-06

Some of the earliest ukiyo-e prints show puppets. A series by Masanobu, c. 1705-06, begins with a scene of a troupe of puppeteers relaxing before a performance. The other prints from the series show scenes from puppet plays, but they show them as you are supposed to imagine them when you see them in real life: the puppeteers are not visible.

Narihira: The Mirror Scene

By Masanobu, c.1705-06

In the early 1700s the vocal artist and shamisen player began sitting in view of the audience and the puppeteers also began operating in view of the audience. Puppet shows were called ningyo joruri: ningyo = dolls or puppets, joruri = chanting to shamisen music. Joruri performers were sometimes also called gidayu performers after the founder of the style.

The puppets became larger and more complex and by the 1730s the system of three operators had evolved. This ningyo joruri was successful at first, but had difficulty competing with the more flamboyant kabuki. The art was preserved and perfected by puppeteers on Awaji Island and had established a foothold in the big cities again by the end of the century. The name bunraku came from the name of an Osaka puppet theatre established in 1805. Puppet theatre was more popular in the Kyoto/Osaka region than in Edo, but enjoyed success in Edo as well.

Beauties with Bunraku Puppets, Twelve Month, Moon Viewing Party after September 9th

By Kunisada, 1854

The early style of puppets, with one operator, continued to be used at local festivals and by amateur performers.

Boys Performing a Puppet Show

By Shigemasa, c.1770

Collection of the MET

Small Theatres

The three official Kabuki Theatres were the grandest and most famous theatres, but not the only theatres in town. Smaller theatres featured both professional and amateur entertainers. Joruri (gidayu) performances, consisting of a singer(s) accompanied by a shamisen player were popular. They performed the music from the puppet stories, but without the puppets.

A shamisen player and four Gidayu performers

Contemporary Full House Changing Pictures

By Chikanobu, c.1880

From the 19th century on female performers known as onna-joruri or onna-gidayu performed in this concert form alongside men.

A woman accompanies a child performer

Contemporary Full House Changing Pictures

By Chikanobu, c.1880

Story tellers also entertained people in the streets and in small theatres. Rakugo is a storytelling art where a lone performer sits on a stage holding a fan and tenugui (small towel) as props and tells a long story, which could be a comedy or drama.

Rakugo storyteller Sanyutei Encho I (1839-1900)

Contemporary Full House Changing Pictures

By Chikanobu, c.1880

Other entertainers performed acrobtics, juggling, dancing, etc. Local theatres in Edo and throughout the country presented Kabuki plays, many by amateur actors. There were even Kabuki plays performed by children.

Nature

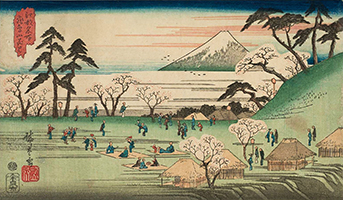

The people of the Edo Period appreciated nature and enjoyed being out in the many green spaces the cities had to offer. Outings to view cherry blossoms in the spring, or autumn leaves were especially popular, as was viewing the full moon. People also went boating for a respite from the summer heat.

Cherry-blossom Viewing at Asuka Hill

By Hiroshige, c.1855-56

One festival that took moon viewing as its premise was held at Takanawa, on the outskirts of Edo by the sea shore. The Festival of the 26th Night involved all-night festivities by the shore with street entertainers and many food stalls. One print showing the event includes fireworks being set off in the bay. Some people went out in boats. All were waiting for the new moon which would appear briefly on the horizon at dawn.

Waiting for the Moon on the Twenty-Sixth Night at Takanawa

By Hiroshige, c.1820s

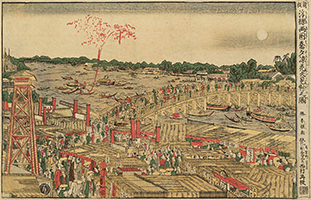

In the summer two firework companies competed with big fireworks displays over Ryogoku Bridge, a long bridge spanning the Sumida River. Fireworks were held off Ryogoku Bridge during the summer from the 1730s onward. The first fireworks of the season marked the opening of the river to pleasure boats and subsequent displays might be held on any clear summer night. The season ended with another display on August 28th. Tea houses and small vendor booths around Ryogoku were allowed to stay open late into the evening. Spectators filled the bridge and those who could afford to rented pleasure boats to enjoy the show from the water, the coolest place to be during the summer heat.

Watching Fireworks in the Cool of the Evening at Ryogoku Bridge

By Hokusai, c.1780s

Festivals

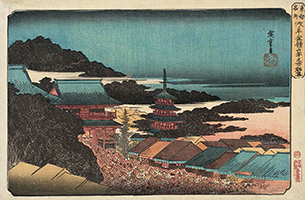

Edo residents didn’t need to go to the theatre to find excitement and entertainment. Festivals of all sorts were held year-round in Edo. Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, many of which were very large complexes, sponsored entertainment for special occasions and hosted festivals, which always involved vendors of treats, toys and souvenirs setting up in and around the temple grounds and could also include anything from putting a prized temple possession on display to holding a fantastic parade.

Crowd at the Year-end Fair at Kinryûzan Temple in Asakusa

By Hiroshige, c.1832-38

The most important festival of the year was the New Year’s Festival. The New Year’s traditions were too numerous to mention them all, but they included special decorations, special food, exchanging cards, giving money or gifts to children and forgiving debts. New Year’s games included children flying kites and women and children playing a battledore game with paddles and a shuttlecock (like badminton with wooden paddles).

Sacred Dance at the Shinmei Shrine at Dawn on New Year’s Day

By Hiroshige, c.1847-52

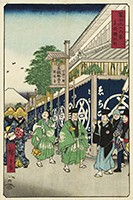

It seems from the prints that streets were filled with entertainers at New Year. This design shows a shop decorated with pine branches on the building and trees placed temporarily outside. Entering from the right is a daikagura troupe who will drive away evil spirits with a lion dance (shishimai) to flute and drum music. They might also do a juggling and balancing acrobatic act. In the center are a manzai duo, performers who would sing and dance or perform comedy routines in which one played the straight man and the other the fool. At left are two female musicians who played shamisen and sang.

The Suruga District in Edo

By Hiroshige, 1858

The other really big festival time included a parade. The Sanno Shrine was host to the Sanno Matsuri (festival) and the Kanda Shrine to the Kanda Matsuri. They were Edo’s two most important festivals. Both were held annually until 1680, after which they were held on alternate years.

The Sanno Festival Parade at Kasumigaseki

By Hiroshige, c.1840-42

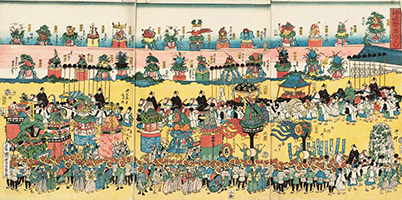

These festivals were big affairs lasting several days and featuring an impressive parade composed of floats and portable shrines provided by various Edo neighborhoods. The parades would wind their way through the streets from the shrine to Edo Castle where they would be allowed into the castle grounds so that the shogun and his family could view the parade. This was a very special occurrence as it was the only time large numbers of chonin were permitted into the castle grounds.

The Kanda Festival Parade, By Yoshikazu, 1859

The two shrines still hold these festivals on alternate years. This year is the Kanda Matsuri on May 11-12. The Sanno Shrine was renamed Hie-jinja Shrine in 1869 (just in case you’re looking for it).

Sumo

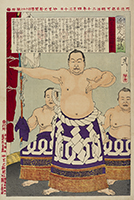

Wrestling matches of various sorts were held in Japan through the centuries, but they were generally between samurai and the objective was to throw the opponent to the ground. These evolved into bouts held within a ring between professional wrestlers where the objective was to push the opponent out of the ring. The sport of professional sumo that we know today originated in the Edo Period in 1684 at the Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in the Fukagawa district of Edo. Tournaments were held in spring and fall and the system for ranking wrestlers began there. The Shinto ritual observed by the wrestlers probably also originated at this time.

Performance of Sumo Fund-raising Tournament

By Kunisada, c.1843-47

Sumo was popular with the chonin and in 1768 the tournaments moved to the Eko-in Temple in Ryogoku, closer to the center of the city. Ukiyo-e prints show these events being held in a very large stadium where the spectators appear to be mostly, if not exclusively male. Sumo wrestlers became celebrities and their portraits indicate that the characteristic sumo physique did not develop until some time after the move to Eko-in Temple.

The wrestler Umegatani Totaro

By Yoshitoshi, 1887

Games

If one wished to stay home there were a large number of games to play. Board games were popular and go boards are often seen in ukiyo-e prints.

Men playing go at Narumi

By Tamenobu, 1918

Sugoroku was another popular board game which involved progressing around a board showing scenes from famous places, often the Tokaido Road, but including many other well-known places. Sugoroku boards were made of printed paper (like the ukiyo-e prints) and were often designed by ukiyo-e artists.

Sugoroku of the famous hot springs at Kusatsu in Joshu Province

By Ryuzaburo, 1892

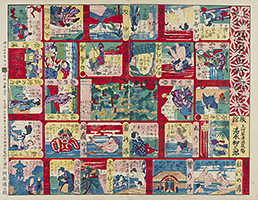

There were a variety of card games too, with the 100 Poets game being among the most popular. This game was based on a famous poetry anthology from the Heian Period, 100 Poems by 100 Poets. The cards in this game show either a poet or a poem and the players have to match them.

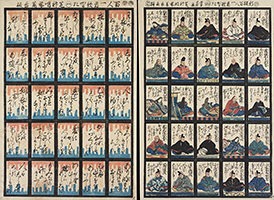

Uncut poet cards

By Yoshikazu, c.1860

Poetry was a hugely popular pastime in the Edo Period. People studied poetry, they wrote poetry, they formed poetry clubs and they held poetry competitions. Some collected poems by well known people the way we used to collect autographs. There were various styles of poetry, including today’s well known haiku, but Kyoka poetry, meaning light verse, was the most popular at the time.

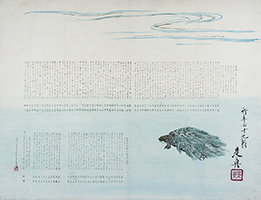

Surimono of a Poetry Club, showing a poem by each member

By Zeshin, 1885

Other popular hobbies which people studied and enjoyed included: ikebana (flower arrangement), origami, the tea ceremony, calligraphy, painting, various forms of music and dance, bonsai and horticulture. Most of these things had been pastimes of the upper classes in earlier periods and had only been taken up by the common people during the Edo Period. The formal tea ceremony, for example, had begun among the elite, and later was given a spiritual dimension when Buddhist monks took up the practice. Tea drinking had spread to all social classes by the 16th century, but the formal tea ceremony was still only practiced by monks and the samurai. During the Edo Period other classes of men began to practice the formal ceremony, but it remained a mostly male practice until the Meiji Period (1868-1912).

Mitate

Literati groups, frequently composed of artists, prosperous chonin and samurai, were also popular. People studied classical texts and showed off their learning with clever literary allusions such as this early print showing a beautiful woman reading while seated on an airborne crane. Those who’d studied the Chinese classics would know that this was a parody of the story of the Chinese sage Fei Zhangfang. He climbed Mount Sung and remained at the summit perfecting his transcendence for over 30 years until he ascended to heaven on the back of a white crane.

Courtesan as Taoist sage Fei Zhangfang

By Masanobu, c.1707

Clever or witty comparisons such as these were called mitate. Many artists designed mitate, although today many of them are hard to spot when we don’t know the cultural context.

In this design Hotei, one of the seven gods of good fortune, is dressed as a courtesan on parade in the Yoshiwara followed by an attendant. Hotei was the god of happiness and little children and he was generally portrayed carrying a sack that was filled with gifts. Here the comparison is to a courtesan who brings another sort of happiness.

Hotei as a courtesan

By Shunsen, c.1820s

Utamaro also designed mitate prints. These are the last two in a series of 12 showing scenes from the Chushingura play (based on the Ako Incident and the 47 ronin) as mitate. The seated man at left represents Lord Kira and the women are the ronin fighting with Kira’s samurai and coming after him. The geisha in the background look as though they’re having a mock battle. Two women on the right are competing in a drinking game similar to rock paper scissors, called fox and hunter. The courtesan handing the customer a large sake bowl is a mitate of Kuranosuke handing Kira a dagger to commit seppuku. It is interesting to note that the customer, the mitate Kira, is identified as Utamaro himself, both by the crests on his jacket and the text above him which reads: “by request Utamaro traces his own ravishing features”.

Chushingura Parodied by Famous Beauties

By Utamaro, 1794-95

This is another mitate of the attack of the Ako ronin on Lord Kira by Kuniyoshi. In this design a child playfully attacks his mother, who wears a kimono decorated with Kira’s crest. One of the ronin appears on the lantern at top right.

Act 11, Mitate Chushingura, By Kuniyoshi, c.1852-54

Censorship

The Kansei Reforms, initiated by Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759-1829), reiterated old edicts and introduced new ones. Matsudaira Sadanobu was the chief councillor and regent for Tokugawa Ienari (1773-1841), who was still a child when he came to power after his predecessor, Tokugawa Ieharu (1737-1786), died in 1786. The Kansei Reforms were largely a reaction to the fairly liberal policies of the administration under Ieharu.

A 1791 edict on commercial publishing stated:

- (1) All texts, including illustrated books and the like, must follow the orders of the magistrate’s office at the time that they are being put into production.

- (2) The publication of written works on matters of the present day and the like is forbidden.

- (3) Writing and publishing stories of vulgar and offensive matters and the like is forbidden.

- (4) All types of erotic books are prohibited

- (5) The real names of the publisher and of the writer must be recorded within the written material.

- (6) The inclusion of useless matters and the production of high-priced and lavish publications is forbidden.

- (7) Illustrated books and the like about affairs of incompetence that have the past as a pretext are not to be produced.

- (8) The lending of manuscripts written in kana and based on rumours is forbidden.

- (9) There will be no sale of anonymous works.

- (10) Book guilds must carry out internal examination.

Please note particularly item #7.

The law had always forbidden the publishers of popular material from producing anything political. This expressly included any samurai lineage that had living descendants. Subjects not connected to the present were considered historical and had been considered acceptable in the past. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), the great leader of the 16th century who had unified Japan, had no living descendants. He was an extremely important and popular historical figure and Tokugawa approved biographies of him had been in publication since almost the beginning of the Edo Period.

At the beginning of the 19th century a new publication on the life of Hideyoshi was issued. Utamaro (1753-1806), famous for his prints of the beauties of the Yoshiwara, and other artists used this serious publication as inspiration for their own, less serious, works. A writer, Ikku Jippensha (1765-1831), produced his own book on the life of Hideyoshi in which key characters were portrayed as animals. Hideyoshi was a snake. Utamaro designed some prints of Hideyoshi and one of his generals in which the famous warriors were shown enjoying the company of women, or boys, in the style of Utamaro’s Yoshiwara prints. This was not only seen as being demeaning to an important historical figure, but it was understood that although the character shown was Hideyoshi, it was a mitate and the reference was to the current shogun, Ienari.

Hideyoshi and his Five Wives on a Cherry-Blossom Viewing Excursion

By Utamaro, c.1803-04

Ienari, the 11th shogun who came to power as a child in 1786, held office for the longest period of any Tokugawa shogun. His rule was marked by excesses and corruption and he depleted the Tokugawa treasury. He had many concubines and fathered 75 children. He reputedly kept a harem of 900 women and he had a Yoshiwara brothel recreated within the castle grounds. He was an unpopular shogun whose rule ended with the Tenpo Famine of 1832-1837.

In 1804 the government reissued the edicts relating to commercial printing and the artists Utamaro, Toyokuni, Shuntei, Shun’ei, Tsukimaro, and the writer Ikku were arrested for violating this law. Utamaro, seen as either the ringleader, or just as the most important or influential of the group, was imprisoned until the trial. At the trial all of them were sentenced to 50 days in manacles.

Artists stopped producing work illustrating Hideyoshi in such insulting ways, though it is clear that the works from the beginning of the 19th century were not forgotten. During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), when the old censorship rules were no longer enforced, artists once again depicted Hideyoshi in a manner suggesting his appreciation for luxury and sexual excess. This set of 3 diptychs by Toyonobu (1859-86) is an almost direct copy of Utamaro’s famous triptych.

New Biography of Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Set of 3 diptychs by Toyonobu, 1885

Comparison of Left Toyonobu Diptych and Utamaro Left Panel

Comparison of Center Toyonobu Diptych and Utamaro Center Panel

Comparison of Right Toyonobu Diptych and Utamaro Right Panel