EXQUISITE NEW WORLDS

Week 1 Class Notes, 7 October 2019

INTRODUCTION TO THE ARTISTS

This course will examine the lives and work of two of Japan’s greatest landscape artists, Hokusai (1760-1849) and Hiroshige (1797-1858). Hokusai had a very long life and remained a productive artist through most of it, creating his greatest works, including the iconic “Great Wave” in his 70s. Hiroshige was a landscape specialist for most of his career and also designed some of his most innovative work later in his life.

Both men were professional artists living in Edo, one of Japan’s two capital cities. Kyoto was the western capital, where the Emperor lived. Edo (now Tokyo) was the eastern capital where the shogun (military ruler) lived. During the course of the Edo Period (1600-1867) Edo became the hub of cultural activity and a new art style called ukiyo-e became popular. Hokusai and Hiroshige both worked in this style.

Both were painters, illustrators and print designers. Both began designing large format woodblock print landscapes around 1830. These turned out to be their greatest legacies and the works that made them famous around the world. Their work influenced subsequent generations of Japanese artists as well as having a significant impact on western artists. The work of each is still important today.

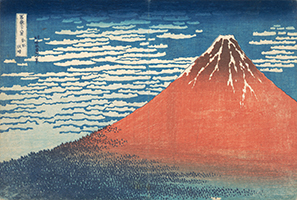

The most famous ukiyo-e print, and perhaps the most famous Japanese work of art, is Under the Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai. It is commonly called the Great Wave and is a popular image around the world. It appears as a symbol of Japan, in internet memes, on t-shirts, greeting cards, etc. It is the one image that Hokusai is most known for outside Japan, though within Japan another print from the same series, Fine Wind, Clear Weather, popularly known as Red Fuji, is equally popular.

The Great Wave

The MET, New York

Red Fuji

The MET, New York

Hokusai was not a landscape specialist and his large format landscape prints constitute a small percentage of his total artistic output. Hiroshige, on the other hand, achieved fame with his first large landscape series and while his work was not limited to landscapes, he continued to design them throughout most of his career. Hiroshige’s most admired works tend to be the rain and snow scenes. Kambara: Night Snow and Shono: Driving Rain from his series Fifty Three Stations of the Tokaido are well known.

Kambara: Night Snow

The MET, New York

Shono: Driving Rain

The MET, New York

If one design can be said to be Hiroshige’s most famous it is Sudden Shower over Shin Ohashi Bridge and Atake, known as Ohashi, from his later series: One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Landscapes by Hiroshige often appear on greeting cards and calendars.

Ohashi

The MET, New York

The continuing popularity of Hokusai and Hiroshige’s work is definitely due to the great talent each possessed, but also to the nature of the woodblock print medium. They are famous for their work in this medium because many copies were produced and widely disseminated. They were popular in Japan, so many copies were made originally. They became equally popular when they reached Europe and America in the later 19th century and were widely collected by art connoisseurs and museums.

Multiple copies of each Japanese woodblock print were produced, but as each was made completely by hand (no printing press) each one is different. Differences can be very slight, or significant. For example, in the Great Wave by Hokusai sometimes the block for the cloud above Fuji is omitted. Other significant differences include variations in colours used or in the areas of shading.

THE EARLY HISTORY OF PAINTING IN JAPAN

Japan’s closest neighbors are Korea, China and Russia. Japan’s earliest cultural period is known as the Jomon, a time when people lived by hunting and gathering and are known for having created the world’s earliest pottery. The Yayoi period began around 300 BCE when migrants from the mainland introduced rice to Japan and farming settlements developed. Around the year 300 a new culture emerged. These people built large tombs in the shape of keyholes and left clay figurines and bronze bells and mirrors. This was the Kofun Period, or the Tomb period.

There was some overlap between the Kofun Period and the following Asuka Period, which is considered to have begun in 538, though some would say 592 or 645. A very significant event occurred in the Asuka Period (or late Kofun, depending on dating): Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 552. Buddhist monks brought sutras and Buddhist art. Buddhism was established in the 7th century and the earliest Japanese art still in existence, Buddhist wooden statues, date from this period. The most significant innovation introduced along with Buddhism was writing and the adoption of Chinese script, known as kanji.

The Bussetsu-ho-kyo Sutra segment

, written in the Nara Period (dated May 1st, 740) in the Tokyo National Museum, is written in kanji.

The Asuka period was followed by the Nara Period (710-784) when Nara became the first permanent capital city, and then the Heian Period (794-1185) when the emperor moved the capital to Kyoto, which remained the capital and home of the emperor until 1868. Buddhism spread during the Nara Period and with it Buddhist pictorial art which was used to help to explain Buddhist doctrine. Buddhist sutras were written on long scrolls that would be unrolled bit by bit as they were read. By the Heian Period illustrations were being included with the sutras on these hand scrolls. The Buddhist art of Japan copied the style of Chinese Buddhist art.

Native Japanese phonetic writing systems called kana had developed by the Nara Period. These, along with kanji, are still in use today and are often combined within the same document.

The Jigoku Zoshi (Scroll of the Hells)

in the Tokyo National Museum is written in a kana script, but includes some kanji. It is expressively illustrated.

Art, poetry, and literature flourished during the Heian Period. Emakimono (picture scrolls) illustrating secular subjects were popular.

This segment of an Emakimono from the Heian Period

features delightful caricatures of animals engaged in human activities. Shown from left to right are: a frog, a monkey wearing a nobleman’s hat, another monkey wearing clothing made from leaves, a fox and another frog:

The Gaki Zoshi (Scroll of Hungry Ghosts)

, also from the Heian Period, was painted in black ink with colour. Emakimono are intended to be viewed from right to left, just as Japanese script is read from right to left.

The Emakimono above are all painted in Kara-e (Chinese style). Be sure to click on “other photos” to see all of the images.

Artists associated with the Heian court also painted in a style called Yamato-e (Japanese style). The Genji Monogatari (The Tales of Genji) Emakimono, created c. 1130, serves as the classic example of Yamato-e art. It is the earliest surviving emakimono of a non-Buddhist subject, presenting text and pictures from the Tales of Genji stories written by a court lady about 100 years earlier. It is believed that there were originally 20 scrolls for a combined length of about 140 meters, containing text and over 100 paintings. Today only 4 of these scrolls are known to exist.

The images used in class came from Wikipedia: The Tale of Genji

The Genji Monogatari scrolls are painted using the Tsukuri-e technique. An artist drew the design and indicated what colours went where, a painter added thick layers of colour, obscuring the original drawing, and the artist then added details such as facial features. The paper was entirely covered in heavy pigment.

The Yamato-e (Japanese style) featured in the Genji Monogatari scrolls makes use of the Fukinuki yatai (blown-off roof) style of composition where an interior scene is viewed from above as though the roof didn’t exist. It also makes use of the Hikime Kagibana technique in which faces lack individual characteristics and are always seen at an angle (people never look directly at the viewer).

The Genji Monogatari scrolls were created during the Heian Period and illustrate a novel set in that period. They show us what the interiors of aristocratic homes likely looked like. We see fusuma (sliding doors) with landscapes painted on them and we see byobu (folding screens).

The only extant byobu from the Heian Period is painted in the Chinese style and shows a young nobleman visiting an old hermit in a hut.

Chinese art and artistic styles were incredibly influential in Japan through much if its history. Both the style and sometimes the scenes themselves were copied. We looked at some examples of Chinese hanging scrolls:

And we looked at some examples of Japanese hanging scrolls in the Chinese style:

It should be noted that calligraphy was an important art form and that it was common for an accomplished calligrapher other than the artist to add a poem or text and to include their signature on the piece.

The above landscape illustrates an interesting facet of Japanese landscape painting. Not only did they paint in a Chinese style, but they often copied the Chinese landscape directly:

Image from Wikipedia

EARLY HISTORY SUMMARY

By the end of the Heian Period Japanese artists were painting fusuma (sliding doors), byobu (folding screens), emakimono (hand scrolls) and kakemono, also known as kakejiku (hanging scrolls).

Most painting was in one of two styles:

Kara-e (Chinese) featuring calligraphic brushwork, Chinese themes, and rugged Chinese landscapes.

Yamato-e (Japanese) style featuring rich colours and Japanese themes, particularly about life at the Emperor’s court.

An example of the Kara-e (Chinese) style on fusuma.

Kennin-ji Temple in Kyoto

An example of the Kara-e (Chinese) style on byobu.

Byobu often came in sets of two screens.

Attributed to Shubun from the 15th century (Muromachi Period)

Tokyo National Museum

An example of the Yamato-e (Japanese) style in an emakimono (hand scroll) can be found in the Tokyo National Museum. This is a segment of

Murasaki Shikibu Nikki Emakimono (Illustrated Diary of Lady Murasaki)

from the 13th century.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOSA AND KANO SCHOOLS

Artists of the Heian Period did not sign their work. Artist’s signatures or seals began to appear on paintings and calligraphy in the 14th century.

In this

Winter Landscape by Sesshu (1420-1506)

from the Muromachi Period the artist’s signature is in the top left with his seal directly below it.

Artists might use only a signature, only a seal, or both together.

The addition of signatures to paintings indicates that certain artists were rising in stature and the consumers of art were probably concerned about buying from the more prestigious artists.

Artists learned their craft by apprenticing with a master. In this way art families and art schools formed. Families worked in a particular style and the successful ones formed art schools. A senior, accomplished artist was the head of the family. He (and they were always men) would need talent, but also a degree of entrepreneurial and managerial skills. He oversaw the operation of a workshop with apprentices and employees. The positon would usually be passed on to a son, but if there was no son, or at least not one with the required skills, a talented apprentice might be adopted into the family. Individuals who had successfully completed their training within the school would be allowed to use the family name as part of their art name.

In the latter Muromachi Period two dominant art schools emerged: The Tosa and the Kano.

The Tosa School carried on the Yamato-e artistic tradition begun in the Heian Period. They were known for highly stylized paintings, mostly of court life, and the use of rich mineral pigments and gold, particularly in the emakimono format. They received most of their patronage from the Emperor’s Court and the nobility.

This illustration from the

Genji Monogatari, Nio no Miya

, is attributed to Tosa Mitsuoki (1617-1692).

The Kano School spcialized in art for interior spaces, particularly fusuma and byobu. They received much of their patronage from the Ashikaga shoguns and later military rulers. They used the Kara-e (Chinese style) to express wealth and power with images of Chinese cultural heroes, or flora and fauna of the four seasons, painted against lavish gold-foiled backgrounds.

This byobu of a

Cypress Tree is by Kano Eitoku, 1590

. Please click on “other photos” to find the image of the second screen of the pair.

The Kano School became a large organization with branch workshops in different locations. They were able to complete large artistic commissions. Their clients included Buddhist Temples and Shinto Shrines, The shogun, daimyo, and their senior retainers, as well as wealthy commoners. For example, the Kano School provided all of the paintings for the interior of the Ninomaru-goten Palace at Niji Castle, Kyoto, when it was built by the Tokugawas at the beginning of the 1600s.

The last Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Submitting his abdication in the Great Hall of the Niomaru-goten Palace

Painting by an unknown artist

The same room today

Another room in the Niomaru-goten Palace